Flash in the Pan

By DAVE BERRY

His name was Walter Wallace Gilonske. He told Grandma Berry she could call him "Flash." He was a lonely airman who looked like he could use a meal, and she found him hitchhiking on the Susank Road. His big smile must have convinced her to stop.

He had walked far, hoping to escape the clutches of the military for a weekend. He hadn't had a home-cooked meal in awhile and must have reminded Grandma Berry of my Dad, who had been in the Army since before Pearl Harbor and was on the East Coast preparing to sail for England with the 3rd Armored Division and its Sherman tanks. She invited the young airman to hop in and come home with her.

Flash, a sergeant in the Army Air Corps, was a waist gunner on the 11-man crew of No. 42-6330, a newly minted B-29 Superfortress. The big plane was one of 1,620 B-29s churned out by Boeing's Wichita factory in the final two years of the war.

The 58th Bomb Wing, formed on the Kansas plains, was concentrated on four bases - the Great Bend Army Airfield, Walker Army Airfield near Victoria, Smoky Hill Army Airfield in Salina and Pratt Army Airfield. Fresh reinforced concrete runways sliced through fields of wheat stubble, welcoming the big new bombers that weighed 30 tons each - double that when loaded with fuel, bombs and crew.

Soon, they would introduce the B-29 to combat over Japan. But from July 1943 until March 1944, they filled the Kansas sky with contrails and the roar of their big engines as they flew in giant formations on practice missions to the Gulf Coast.

Flash enjoyed his day with my grandparents, and they invited him back. Aunt Julia, who was 14, wasn't too sure about the outgoing 23-year-old airman she first discovered tapping out tunes on her piano, but he must have won her over.

Grandpa Berry, slowed by diabetes, struggled to work the farm while Dad was away, and Flash offered to help. Hitchhiking 30 miles from the base to the farm, he showed up on many weekends that winter. In exchange for fried chicken and a small wage, he helped granddad feed the cattle, break ice on the pond... whatever needed doing.

Around the Berry's kitchen table, over hot cherry pie made with rationed sugar and topped with homemade ice cream, they shared the stories of their lives. Flash was born in New York City, where his parents settled after leaving Poland. At 17, he lied about his age to work on a British-flagged freighter, the SS Gypsum Prince, hauling cargo between Nova Scotia and Boston. At 20, he enlisted in the Army Air Corps, a year before America entered the war. In 1942, he took a wife, Dorothy, who lived in Minneapolis with their newborn son.

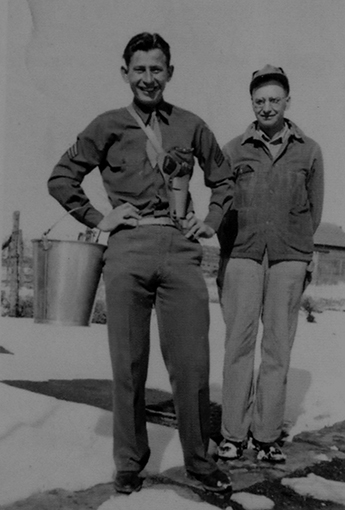

Flash trained through the winter of 1943-44, breaking free to spend weekends with the Berrys on the farm. On a final visit, standing beside my grandfather in the snow, he smiled for a photo with his hands on hips, a holstered Colt .45 pistol strapped across his chest, a shiny milk pail hanging from his arm.

Then, on March 10, 1944, Flash and the 58th Bomb Wing departed Kansas for good. His B-29, piloted by Maj. Charles Hansen and assigned to the 444th Bomb Group, was among the first to arrive at their new base in India. They were still a long way from Japan... too far even for the very long range bombers. They needed a base in China. For two months they "flew the Hump," pushing their Superfortresses - packed with bombs, fuel and supplies - up and over the towering Himalayas to equip a forward operating base at Chengtu, China.

Christened the "Fickle Finger," nose art painted by the crew's best artist, No. 42-6330 flew regular supply runs. They flew unmolested until April 26, 1944. when Japanese fighter planes made their first interception of B-29s over the Himalayas. Only one plane, the Fickle Finger was shot up, and one crewmember, waist gunner Walter Gilonske, was wounded.

You wouldn't have known it from his first letter to the Berrys. Four days after being wounded, he inquired about their health, described the sights, sounds and people of India and wrote of the heat that baked his straw-roofed hut. "As for myself, I'm feeling swell," he said, then asked that they relay his best wishes to all those he had met at the farm. Never did he say he was hurt, unless you read between the lines, "Say," he wrote, "do you still think I'm a crack shot with a .45 cal. P.S. I'm not."

In his second letter May 7, he wrote three pages on "this strange, colorful land" with "fascinating" customs, languages, dress and religious beliefs. "Have you heard from your boy lately?" he asked. "Hope he's fine. Love, Flash." That was his last letter, but my Grandma and Grandad heard from Flash from time to time when messages on Indian and Chinese currency - addressed and stamped like postcards - showed up in the mailbox.

Flash was busy flying bombs and fuel into China, and on June 5, the day before the Normandy invasion, B-29s reinforced the Chinese Army under Chiang-Kai-shek battling the Japanese in China. Five bombers were lost in that action.

On June 15, in the first strategic raid over Japan, flying from India and refueling in China, another bomber was shot down and five were lost to operational accidents. The fuel, so painstakingly stockpiled in China, was expended. B-29 operations were suspended until more fuel and bombs could be flown over the mountains. In July, more planes were lost in small raids - two, four and then another four. On Aug. 10, 31 B-29s bombed an oil refinery in Sumatra, the longest single-stage flight by combat aircraft in WWII - 3,600 miles. One B-29 ran out of fuel and crashed.

Back on the farm, the dry heat of a late August had set in. Granddad, with harvest over, waited out the hot summer listening to war news on his Atwater Kent radio. Letters from my Dad told him little. Censors wouldn't let him mention the bloody battles of the 3rd Armored as it stormed across France, bypassing newly liberated Paris and advancing toward Belgium. Nor could Dad tell his father of three men lost from his small unit, including his best friend Gordon.

And now the letters from Flash stopped. In another year, the war would end, Dad would come home and life would return to normal. But my grandparents would never again hear from the young sergeant.

Of 130 B-29s brought to India by the 58th Bomb Wing six months earlier, only 75 remained. On Aug. 20, 1944, 61 of them took off on a daylight bombing mission against the Imperial Iron and Steel Works at Yawata, Japan. They dropped 96 tons of bombs and shot down 17 enemy planes. But nearly a quarter of the bombers - 14 B-29s - were lost.

Another 13 bombers, a small formation that included the Hanson crew in the "Fickle Finger," left late in the day on an ill-fated night attack on the same Iron Works. It was a disaster for the bomber wing. Twelve B-29s were lost, and only one bomber would limp home. The "Fickle Finger" survived the raid but crashed and exploded against the face of a cliff in the mountains of China. Flash Gilonske and all those aboard were lost. One man was listed as rescued, but in reality he was on sick call and missed that mission.

Today, the concrete runways that hosted the B-29s form the skeleton of the Great Bend Municipal Airport. At its northern edge is B-29 Memorial Plaza, where some of the crews lost in the war are recognized. One plaque salutes the "Fickle Finger."

Flash, like more than 400,000 of the 16 million service men and women who fought in World War II, never lived to tell his story. And my grandparents, who welcomed the young airman into their home and into their hearts, never read his final chapter.

Dave Berry is the retired editor of the Tyler Morning Telegraph. This column ran on Feb. 24, 2016

Photo: Sgt. Walter "Flash" Gilonske and James Walter Berry on the farm in Kansas during the winter of 1943-44.